The Misunderstood Roots of FRP Can Save Programming

This essay was presented at Salon de Refusés 2019, colocated with <Programming> 2019, in Genoa, Italy on April 2nd, under the title Visual Denotative Programming. The talk was not recorded but you can watch a (rough) practice talk here. The slides can be found here.

For many years I been searching for the perfect paradigm for programming user interfaces. Like many others, I fell in love with FRP with the rise of ReactJS and spent a few years searching for the perfect reactive model. Eventually, I found my way back to the original work on FRP by Conal Elliott. It took me almost a year to make sense of it. This essay attempts to make Conal’s vision more understandable to less mathematically-oriented programmers, and also show how this perspective could be the foundation for a new era of programming, not just with user interfaces, but also multi-node computing, storage, machine learning, etc.

This essay assumes familiarity with:

- JavaScript syntax, including Promises,

- a web FRP library, such as ReactJS, VueJS, CycleJS, Redux, or Elm,

- and minimal ML/Haskell syntax, including the

Maybetype.

Modern Reactive Web Programming

I fell in love with ReactJS in late 2014. The view is a pure function of state. It was so obviously right.

But of course React isn’t the whole answer. It’s just a view library that keeps the view in sync with state. It’s left open how you manage that state.

Inspired by the Elm Architecture, Redux became the popular answer to the state management question. It puts the state of the entire application into a single object. To affect this global state object, your HTML event handlers emit “actions”, such as {"type": "newTodoItem", "description": "Clean my room"}. You then define a reducer function that modifies the global state each time it receives an action. This architecture initially made a lot of sense to me. One big sell is that its global state object is easily serialized, which enables hot reloading and time-travel debugging.

Unexpectedly, when I tried to make sense of large Redux projects, I found myself getting headaches. I found it difficult to understand how the app fit together, which parts affected which other parts. I began to see that the Redux architecture was simulating global mutable state in a seemingly immutable and functional setting, ruining modularity and comprehensibility.

I eagerly slurped up each new React-inspired framework, such as VueJS and CycleJS, to see if they could finally be the “full solution” to interface development, but none felt quite right.

Paul Chiusano suggested I read Conal Elliott, the creator of the FRP paradigm. Paul claimed that React and the other JS-based FRP libraries weren’t even ‘true’ FRP. I didn’t like to hear this. I loved React and the FRP I knew. I was reluctant to read a stodgy paper from the 90s. But I trusted and respected Paul so I gave it a go.

It was a lot of mathematics and strange symbols. What’s a “least upper bound” and “pointed CPO”? My eyes glazed over. I tried a more recent paper he wrote on FRP, but it was full of scary Applicative Functors and Monads. I gave up.

However, I couldn’t escape HN comments alluding to “real” or “original” FRP. They were annoying enough to send me back to Conal for another try. This time I printed out all his papers, determined to make sense of them!

I took my time with the unfamiliar mathematical and typeclass concepts. With a lot of focused reading, it finally began to click.

DCTP: Denotative Continuous-Time Programming

It’s important to distinguish between the many flavors of FRP. The name originally comes from Conal Elliott and Paul Hudak’s work in the 90s . The term has since been stretch so far beyond its original meaning that Conal has retreated to a new phrase to describe his original vision: Denotative Continuous Time Programming (DCTP).

D is for Denotative

The D of DCTP has similarly nuanced intellectual roots. It stands for “denotative”, a term Peter Landin proposed as a an alternative to “nonprocedural”, “functional” or “declarative”, which lack precise definitions. A denotative programming language is one where:

(a) each expression has a nesting subexpression structure,

Unlike most programming languages which have a mix of statement commands and expressions, denotative programming languages live solely in the world of expressions. For example, instead of if-statements, there are ternary expressions. Instead of loops, recursion. Nested mathematical-like expressions are the only way to construct programs, and thus a program is simply one large, nested expression.

(b) each subexpression denotes something (usually a number, truth value or numerical function),

Additionally, the components of denotative languages must denote some mathematical object. This was directly inspired by Chris Strachey and Dana Scott’s work from the early 1970’s on denotational semantics, an approach to modeling programming languages with mathematical objects. But where denotational semantics was originally created as a way to analyze all programming languages, denotative programming languages are a very specific kind of language, purposefully designed to be well-suited for mathematical reasoning.

For example, a map (“object” in JavaScript, “dictionary” in Python) in a denotative language could denote a mathematical function of keys to Maybe values. The empty map would be key => Nothing, returning Nothing for any key. Inserting a key, value pair could be: (map, key, value) => (key' => key === key' ? Just value : map(key)), which wraps an old map function with a new key comparison, but delegates to the old function for the remaining keys.

This map need not be implemented in such an inefficient way for a language to qualify as denotative. Denotations are specifications, describing the what, but leaving the how open. Implementations of denotative languages can be as as non-denotative as efficiency concerns demand. A common misunderstanding of the denotative approach is that it’s impractical to eschew statements, because statements must be executed eventually for computation to be carried out. This is of course true, but the distinction is that in denotative languages, statements live in the implementation of the language instead of in the language itself.

For example, even non-denotative languages have functions like pow, sqrt, log, sin, and cos, which denote their equivalent mathematical operations. Users of these functions are free to treat them as true expressions, without having to worry about their potentially non-denotative implementation details. Do they use specially-designed hardware? Loops? It doesn’t matter: users are free to write log(x) + sin(y) and the language’s compiler or interpreter will execute these expressions with whatever non-denotative algorithm is most efficient, as long as it meets the denotative specification for log and sin.

From the denotative perspective, anywhere an operation does not meet its denotative equivalent is a bug. This would include anywhere floating-point math is used, which causes, for example, 0.1 + 0.2 to equal 0.30000000000000004. In other words, all the quirks of math you need to learn above and beyond what you already learned in algebra class is considered incidental complexity. On the other hand, non-denotative languages aren’t trying to be denotative, so it’s not entirely fair to rank them according to a rubric they are not aiming for.

(c) the thing an expression denotes, i.e., its “value”, depends only on the values of its subexpressions, not on other properties of them.

The final criteria is that expressions in denotative languages are entirely self-contained. There’s no action-at-a-distance. There’s no way to call someValue.update(). For one, that would be a statement. But additionally, all possible ways someValue updates need to be defined in one of the sub-expressions of someValue itself.

In summary, a denotative language is a pure functional language, with the addition of point (b): mathematical denotations.

Benefits of Denotative Programming

Programmers spend roughly 50% of their time reading code, so a language that better lends itself to comprehensibility is a boon for productivity.

Denotative languages better convey the global structure of a program. We can fully understand an expression by its subexpressions, and their subexpressions, recursively. There are no spooky action-at-a-distance side-effects that can manipulate things from afar. We don’t have to read the entire codebase to ensure we understand a single piece; we must merely read its subexpressions, recursively. This allows us to quickly rule out what we do and do not need to read, saving us a lot of time in large codebases. A denotative language resembles a dictionary or encyclopedia, where one can understand an entry by reading it and what it references. A non-denotative language resembles prose, like a novel, which you have to read cover-to-cover to know what happens, even if you only care about one specific character.

These comprehensibility benefits extend to local analysis as well. In denotative programming, the equal sign means what it does in a mathematics textbook: we can replace instances of the left with the expression to the right. This is known as referential transparency. We can safely refactor:

b = f(a)

c = g(b)

d = h(c)

to:

d = h(g(f(a)))

True equality is also a boon for performance optimizations, which is about replacing sections of programs with equivalent but faster sections. When your code is free of operational concerns, the language implementer is able to make more interesting optimizations. The flip-side is that because the denotative approach cuts us off from these implementation details, it lessens the ability of a user of a denotative language to improve the performance of their programs. However, programmer time is often more valuable than CPU time. The Haskell compiler already produces competitive speed and space efficiency for contexts where resources aren’t extremely tight, and hopefully this will continue to improve over time due to better chips and advanced compilation techniques.

Finally, denotative languages offer upgraded support for composibilty and modularity, decreasing the amount of total code required. Conal explains, “Modularity comes from providing information while making as few restrictive assumptions as possible about how that information can be used.” For example, “laziness lets us build infinite data structures, thus not assuming what finite subset any particular usage will access.” The more our code is abstract, general, unspecific, mathematical, and free from operational concerns, the easier it is to use it in other contexts. John Hughes’s Why Functional Programming Matters beautifully demonstrates how the denotative style, particularly laziness and higher-order functions, enable modularity.

Two examples of denotative programming languages are spreadsheets and the denotative subset of Haskell.

Spreadsheets

Spreadsheets are a wonderful sweet spot of power and simplicity, enabling non-programmers to express complex logic. Part of their simplicity lies in their denotative characteristics:

a) There are no statements, only nested expressions.

b) Each expressions denotes a string, number or truth value.

c) There’s nothing else that can affect the value of a cell except its formula and the formulas of its children, and their children, and their children, and …

These limitations allow for a global view of a spreadsheet via the “trace precedents” function, which visualizes cell dependencies:

Haskell and the IO Monad

Haskell is a denotative language, except as it pertains to the IO Monad. Monads are notoriously difficult to understand. I put most of the blame on the IO Monad, which is just one flavor of monad. By themselves, monads aren’t so complicated. They are simply a way to sequence computations, taking the result of one and passing it to the next, in order. For example, JavaScript programmers regularly use the Promise monad without even realizing it as a monad: makeHTTPRequest().then(result1 => doSomething(result1)).then(result2 => doSomethingElse(result2)).

In Haskell, all monads except the IO Monad have valid denotations. For example, the Maybe monad allows the convenient sequencing of a number of optionally-returning computations, returning Just with the result in the case they all succeed and Nothing in the case that any fail.

However, the IO Monad does not denote any mathematical object, but allows for any non-denotative commands to be generated. For example, it allows for reading and writing to the file system, which violates (b) and (c) properties of denotative languages. What’s makes the IO Monad confusing is that it’s allowed in Haskell at all. In Can functional programming be liberated from the von Neumann paradigm? Conal Elliott laments:

“monadic IO” is a way to generate imperative computations (not just I/O) without having to say anything at all about the semantic content of those computations. Rather than retooling our mental habits completely away from the imperative model of computation, monadic IO is a way to hang onto these old mental habits, and use them in a hybrid functional/imperative programming style, in which the imperative doesn’t contaminate the functional, semantically.

The IO Monad is particularly confusing because the Haskell community, purported to be the bastion of denotative programming, seems to be content with this non-denotative solution:

In a sense, I see us as in a worse position than before. Since the adoption of monadic IO, it’s been less immediately apparent that we’re still enslaved, so there’s been much less activity in searching for the promised land that the prophet JB [John Backus] foretold. Our current home is not painful enough to goad us onward, as were continuation-based I/O and stream-based I/O. (See A History of Haskell, section 7.1.) Nor does it fully liberate us.

What is the alternative to the IO Monad? How are we to do all the non-denotative operations, such as opening and closing files and sockets, and reading and writing from the console and the database? The alternative is to find clever abstractions that will push these non-denotative operations into the implementation of a fully denotative language. We’ve done it before:

Underneath the implementation of our current functional abstractions (numbers, strings, trees, functions, etc), there are imperative mechanisms, such as memory allocation & deallocation, stack frame modification, and thunk overwriting (to implement laziness). Every one of these mechanisms can be used as evidence against the functional paradigm by someone who hasn’t yet realized how the mechanism can be shifted out of the role of a programming model notion and into the role of implementation of a programming model notion.

My favorite example of shifting from the IO Monad to a denotative paradigm is what DCTP did with reactivity.

Denotative Reactivity

Denotative languages were naturally best suited to batch calculations with one input and one output, such as compilers. A notorious weak spot was reactive systems that needed to accept and respond to inputs over time, such as robots or user interfaces. For example, a user interface must update itself in response to button clicks and keyboard presses. Before DCTP, these updates were made via some kind of statement. In Haskell it would’ve been the IO Monad. In JavaScript, we used JQuery for DOM mutations.

However this changed with ReactJS. React allows us to specify UIs as a pure function of state. We can now leave it up to the React library to handle the non-denotative DOM mutations for us. That’s not to say that we’ve gotten rid of non-denotative computation – they still happen via virtual dom diffing and patching – but we’ve shifted those computations down the stack, resulting in a cleaner, high-level denotative computation.

While they were inspired by DCTP, React and other modern FRP libraries violate many denotative principles. For example, most of these libraries allow for mutable state or simulate it with the Redux / Elm Architecture. A very common misconception is confusing DCTP with its implementation details. Conal again:

Every time you hear somebody talk about FRP in terms of graphs or propagation or something like that, they are missing the point entirely. Because they are talking about some sort of operational, mechanistic model, not about what it means.

The builder of a DCTP framework or library may decided to choose a DAG as an internal data structure, but they may choose an entirely different underlying evaluation strategy. In fact, a DAG is likely the wrong structure for DCTP because DAGs are (definitionally) acyclic, and DCTP often requires cycles to represent the full range of user interfaces.

The CT is for Continuous Time

Let’s continue our study of DCTP with the next two letters. This will also give us the opportunity to further explore the denotative approach, modeling graphics and animations denotatively.

One of the inspirations for DCTP came in the form of a question from John Reynolds. It roughly amounted to:

What would it be like to program in continuous time?

This is a wonderful question, but it’s hard to answer it directly, partly because time is hard to visualize. Let’s come at this via a slightly different question and then circle back to time:

What’s the difference between a bitmap and SVG image?

Continuous Space

In layman’s terms: if you zoom in a bitmap graphic, it will get all pixelated. But if you zoom into an SVG (Scalable Vector Graphics), it will remain crystal clear.

Image Source: StickerYou Blog

This is because a circle in a bitmap graphic is just an array of pixels, so if you zoom in, the computer has no choice but to “blow up” each pixel. However, with a circle in an SVG, the computer always remembers it’s a circle and thus will be able to show it at whatever resolution you want. SVGs are “resolution-independent”.

SVGs retain all the relevant info until the very last moment when the computer finally has to put the picture on the screen; then it turns your circle into a bunch of pixels. On the other hand, a bitmap is a bag of pixels always, and thus when you want to zoom in, it’s stuck with too little information (it doesn’t know those pixels started out as a circle) to give you what you want. It’s gone to pixels “too early.”

What is a graphic?

Let’s get denotative with our definitions. A graphic is function from x and y coordinates to colors. You give it an (x, y) pair; it gives you a color.

Here’s the difference between bitmaps and SVGs: what kind of numbers make up the (x, y) pairs?

With bitmaps, it’s a pair of integers (Int, Int) -> Color, while with SVGs it’s a pair of real numbers (Real, Real) -> Color.

A bitmap is a graphic over discrete space. This means that you can count the pixels one by one. There are no pixels in between two adjacent pixels. This is why we have trouble zooming in: we must create more pixels in between where no pixels yet exist.

An SVG is a graphic over continuous space. Between any two points in an SVG there are an INFINITY of points. It wouldn’t even make sense to discuss adjacent points, because you could always find more points in between any two points. This is why SVGs scale so well. SVG graphics know the values of infinitely many points, so they are infinitely flexible.

Here’s a very simple graphic that describes an infinity of points. For all points, the color is red.

// Example 1

const red = [255, 0, 0, 255]

const example1 = (x, y) => red

The code for examples 1-5 in this essay reflect the initial JavaScript I wrote, which you can play with here. However, that code was purposefully simple, and thus too slow for graphics larger than 150x150 pixels. It was calculating the color for each pixel on the CPU! Underneath each example, I link to a JSBin with the roughly equivalent (but much uglier) code running on the GPU via gpu.js. However, the current version of this essay replaces them with equivalent SVGs so as to be easier on your computer’s processor.

Here’s another: a green circle with radius 50, centered at (100, 150).

// Example 2

const green = [0, 255, 0, 255]

const white = [255, 255, 255, 255]

function circle(centerX, centerY, r, color) {

return (x, y) => Math.pow(centerX - x, 2) + Math.pow(centerY - y, 2) < Math.pow(r, 2) ? color : white

}

const example2 = circle(100, 150, 50, green)

Continuous Time

Now let’s return to the original question that inspired FRP:

What would it be like to program in continuous time?

In most programming, time is discrete. The ticks of time can be counted one-by-one, and there is no time in between adjacent points. For example, JavaScript’s requestAnimationFrame has discrete time ticking along at about 60 times per second.

What is an animation?

An animation is a graphic that changes over time. That is, it takes an x and y as before, but now it also inputs a t for time, and outputs a Color as before: (x, y, t) -> Color. But again, what kinds of numbers are x, y and t? If they are integers, we’re in discrete space and time. Let’s make them all reals, and enter continuous space and time.

Let’s have our green circle drift off the screen to the right. (You may have to refresh the page to see it go.)

// Example 3

const example3 = (x, y, t) => circle(10*t, 0, 50, green)(x, y)

Let’s have it go faster. (You may have to refresh the page to see it go.)

// Example 4

const example4 = (x, y, t) => circle(100*t, 0, 50, green)(x, y)

How about moving in a circle? Let’s use some trig!

// Example 5

const example5 = (x, y, t) => circle(50*Math.cos(10*t), 50*Math.sin(-10*t), 50, green)(x, y)

Why program with continuous time?

Of course, for the computer to render animations on the screen, it must at some point convert the continuous time and space to discretized pixels and ticks of time. So what’s the point of programming in continuous time if it will eventually be discretized?

There are a lot of reasons. The most compelling argument for me is for the same reason we use SVGs: resolution independence. We want to be able to transform our programs “in time and space with ease and without propagating and amplifying sampling artifacts.” We want to discretize at the last possible moment, and stay as abstract as possible for as long as possible.

Behaviors and Events

DCTP extended the denotative approach to handle interactivity, such as mouse and keyboard events. The examples from above were pure functions from x, y and time to color. In DCTP, we call such all such continuous functions from time “Behaviors”.

Behaviors

Graphic of Behaviors from the Hareactive documentation

Behaviors denote continuous functions of time, such as:

- the animations above

- the x-y-position of your mouse

- the constant function

t -> 1 - the Boolean valued function:

t -> t > 10

Events

DCTP distinguishes continuous behaviors from discrete event occurrences, such a mouse clicks. Events denote an infinite list of tuples [(a, Time)], where each tuple contains the event value and the time of its occurrence. Examples include:

- the click event of your mouse

- key press event of your keyboard

- an interval of 3 seconds

Graphic of Events from the Hareactive documentation

DCTP & HTML

Unfortunately, DCTP gets a lot more complicated when we try to extend it to HTML-based user interfaces. While I dream of one-day having a user interface library that’s denotationally a function from position, time, and hardware events to color, it’s more practical today to output HTML.

Our first trouble with HTML comes from keeping our functions pure (side-effect free). Let’s say we wanted two buttons side-by-side. It would seem reasonable to do:

clicks1 = button()

clicks2 = button()

However in a denotative language, clicks1 would have to equal clicks2. Purity requires that calling button multiple times can’t specify multiple buttons. What we need is a way to explicitly sequence buttons and their click events, such as:

button().then(clicks1 => button()).then(clicks2 => somethingElse)

The .then()function (or >= in Haskell) for HTML elements accepts a function from the output of the previous element to the next element in the sequence. You may recognize this structure as a monad. This is the approach most DCTP libraries use to construct HTML interfaces, including the Turbine framework used below.

It becomes tedious to chain together monads explicitly. In JavaScript, we have the await syntactic sugar, but it only works for chaining the Promise monad. In Haskell, we could use do-notation which works on any monad, but JavaScript doesn’t have any generic monadic syntactic sugar. The creators of the Turbine library cleverly co-opt generator functions (function*()) to approximate do-notation for chaining HTML elements. The order of the HTML elements mirror the order in which they are yielded.

The final difficulty with the following examples is the quirky way that the Turbine library avoids memory leaks. The Turbine library uses an approach based on the work of Atze van der Ploeg which requires specifying, in a monad, the point in time you’d like the computation to start accumulating state. So below there are two distinct uses of yield: the first is to add an HTML element to the sequence, and the second is to start accumulating a stateful behavior.

A Turbine Counter

0

const counter = function*() {

// yield a button as the first HTML element in the sequence.

// It returns an object of all possible event streams on that button.

// We destructure `clickEvent` as the stream of all click events on the button.

const { click: clickEvent } = yield button("Count!");

// Calculate the number of clicks on the button.

// accumFromComponentCreation is like fold or reduce, but over streams.

// It is a stateful behavior, so yield here specifies to

// start accumulating when the component is created on the screen.

const clicksCountBehavior = yield accumFromComponentCreation(

(n, m) => m + 1,

0,

clickEvent

);

// yield a span with the clicks count

yield span(clicksCountBehavior);

};

A Redux Counter

Contrast this approach with a Redux counter. In Turbine, we put everything you need to know about clicksCountBehavior in a single place. Here state’s definition is spread all over:

- It is initially set to

0in the parameter of the reducer function. - It is modified below in reponse to the

'INCREMENT'action. - It is also modified via the button’s onclick event triggering the the

'INCREMENT'action.

const counterReducer = (state = 0, action) => {

switch (action.type) {

case 'INCREMENT':

return state + 1;

default:

return state;

}

}

var Counter = () => (

<div className='redux'>

<h1>{store.getState()}</h1>

<button onClick={()=> store.dispatch({type: 'INCREMENT'})}>+</button>

</div>

);

The problems of the Redux approach include:

- State is defined in three places as mentioned above: the inital value, it’s mutations in the reducer (which can also be spread out), and the places in the view which trigger the reducer (also spread out)

- State can be modified in terms of any other piece of state, ruining modularity.

- It ties this all together with string-based message types, instead of richer types, like functions or values.

From a comprehensibility perspective, the DCTP/Turbine’s more structured approach is a significant upgrade. However, the higher-order and cyclic flows that are required to make the DCTP approach work offer their own challenges.

Cyclical Flows

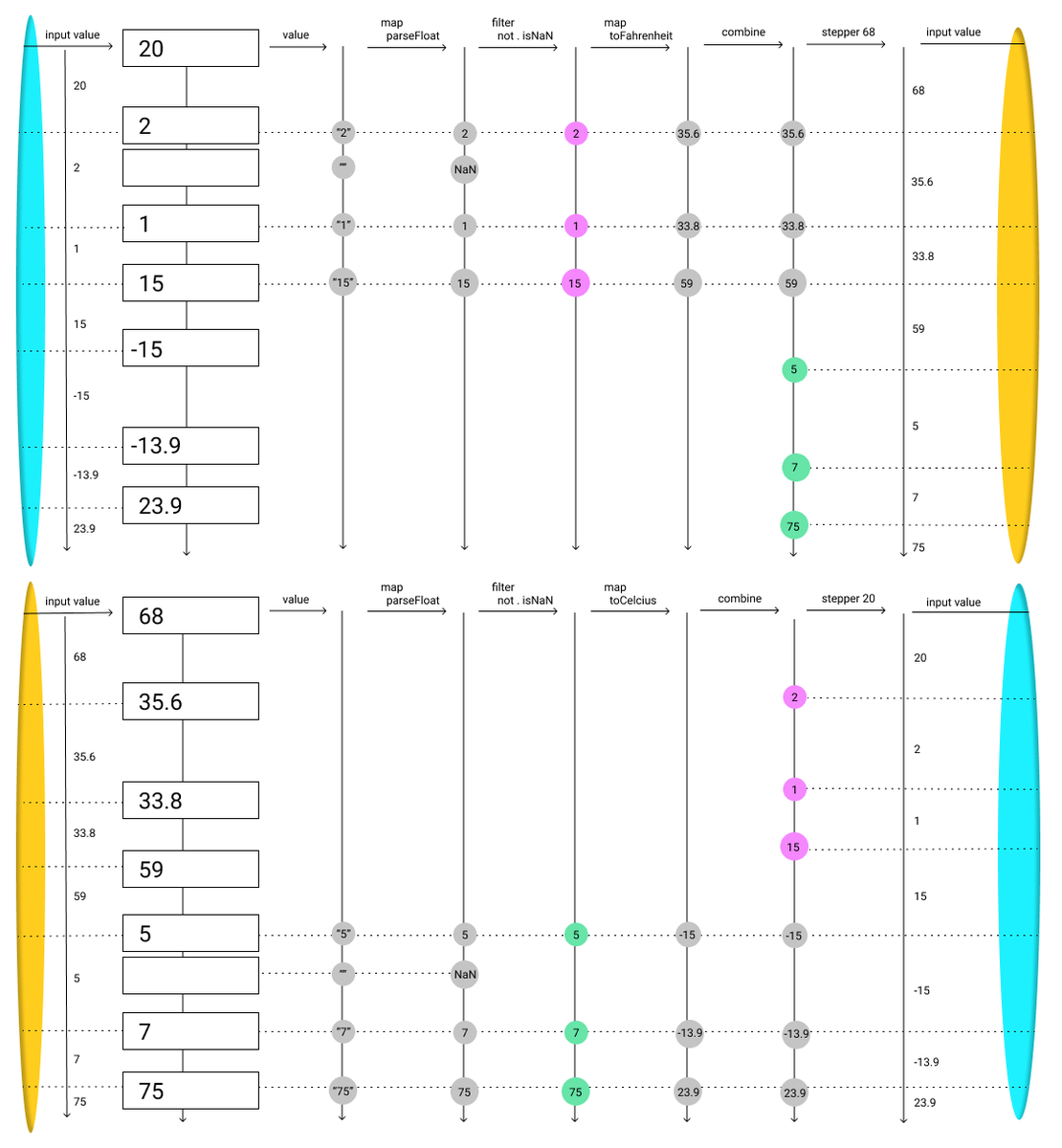

User interfaces often involve cycles, such as in the classic Celsius to Fahrenheit converter application. The app consists of two input boxes, one representing Celsius, and the other Fahrenheit. When either input box is modified, and it’s value is a valid number, the other input box is updated to reflect the corresponding temperature in the other units.

// loop allows us to specify cyclic streams

// it takes a function, and passes the output of itself back into itself

// the first run of the function is bootstrapped with placeholder streams

const temp = loop(

({ c, f }) =>

function*() {

// Add an input box for Celcius

// Get cVal as the Behavior of the box's value

// Set the value of the input box to the Behavior c (defined below)

const { value: cVal } = yield input({ value: c });

yield text("Celcius = ");

// Mirros the Celcius input box for Fahrenheit

const { value: fVal } = yield input({ value: f });

yield text("Fahrenheit");

// cValN and fValN are Events of changes to the respective input boxes

// Parsed as numbers, and filtered for only valid numbers

const [cValN, fValN] = [cVal, fVal].map(s =>

changes(s)

.map(parseFloat)

.filter(n => !isNaN(n))

);

const fToC = f => (f - 32) / 1.8;

const cToF = c => (c * 9) / 5 + 32;

const initialC = 0;

const initialF = cToF(initialC);

// c_ is the definition of c above

// stepper converts an event to a Behavior of the last value of the event

// combines the Celcius input with the Fahrenheit ones, converted to Celcius

const c_ = yield stepperFromComponentCreation(

initialC,

combine(cValN, fValN.map(fToC))

);

// ditto for Fahrenheit

const f_ = yield stepperFromComponentCreation(

initialF,

combine(fValN, cValN.map(cToF))

);

// tie the recursive knot

return { c: c_, f: f_ };

}

);

Visualizing Flows

Even I find the above code hard to read, despite having written it! While this could be seen as a downside of the denotative approach, I see it as a mismatch between the denotative approach and textual syntax.

There’s been interesting work visualizing streams, which I hope to build on. Currently, I’m in the mockup phase, but I hope to build a developer tool experience that will automatically generate a live visualization.

One way to visualize these streams is as a dependency tree, annotated with stream values:

I’m also experimenting with a more left-to-right interface with “wormholes” for far-reaching or cyclic connections:

Ultimately I believe the denotative approach lends itself to a broader range of visualizations than non-denotative approaches. Languages which execute line-by-line, mutating memory addresses are limited to visualizations that look like this:

Because denotative abstractions are higher level than executing arbitrary instructions, their visualizations can better expose their essence. Instead of stepping through each line and watching what happens to memory, we can visualize a map function as list of initial values beside a list of final values. Even when they model dynamic systems such as in the DCTP examples above, denotative programs have a static structure, which allows us to have a global view of data, like in a spreadsheet or dashboard. We are in the early days of applying visualization techniques to denotative abstractions. Today syntax-based denotative languages like Haskell deservedly have a reputation for abstruseness, but I hope that with live visualizations they will one day be known as the easiest to understand.

Beyond User Interfaces

We’ve seen how to apply the denotative approach to build user interfaces, but how far can it scale?

HTTP

How could we fit HTTP requests into the DCTP model?

That’s the wrong question. HTTP requests are too low level. Just like JQuery manually queried and mutated the DOM, HTTP requests manually query and mutate server state.

The same is true of all non-denotative APIs, including databases, files, threads, and sockets. All these abstractions are too low-level for the problems every-day programmers need to solve. Their place is in the implementation of denotative programming systems. The computer’s (or compiler’s) job should be making HTTP requests, reading and writing to files and databases, on your behalf, just like React mutates the DOM on your behalf.

We need to liberate ourselves from the antiquated notions of a “frontend” and “backend”. We need to go higher level and build a denotative model for “whole systems.”

Distributed DCTP

There has been work on distributed reactivity, but not any that truly blurs the line between server-and-client. Even multi-tier languages, languages which span an entire client/server app, still require the user to explicitly annotate which code lives on the server and which on the client. To me, such a distinction feels too low-level. I hope to one day have an extended DCTP that can account for the time between computers without referring to other operational details.

Let’s extend our simple counter button from above to a multi-computer counter button. That is, our counter button will live at a URL, and anyone who loads that URL can contribute to the total clicks count by clicking on the button.

Notice how nowhere in my description of the counter is any mention of frontends vs backends, databases, or HTTP requests. The essential complexity of this problem has nothing to do with such things, and neither should our code for this problem. Those details would be the compiler or runtime’s job.

Here’s a high-level description of what the code could look like: the multi-computer-count is the count of “all computer’s” click events, for “all time”, where “all computers” conveys the merging of streams on various computers and “all time” conveys the persistent, running total storage of this number somewhere.

One important essential complexity detail to keep in mind is that we cannot abstract away the amount of time it takes for information to travel between computers. I find it helpful to imagine interplanetary counter button, where we are counting along with Elon’s Mars colony, 3 light-minutes away.

My current favorite strategy to encode this reality into our denotative model is through the lens of perception. Think about creating this counter button from the perspective of one computer. What is the “multi-computer count” from the perspective of this computer?

It’s the count of the merging of two Event streams:

- The local click event stream from the button on this computer

- The remote click event stream of all other computers click events

So in order to merge local and remote Events steams, we will probably need to lift the local Event stream into a remote one. Then we merge. Then we count. Now we have a remote Behavior, which we can (maybe through some other type munging) put on the screen.

ML != neural networks

Here’s one final example of how the denotative approach could affect another area of programming: machine learning.

In a recent call I had with Conal, he criticized the mainstream perspective on ML. For example, the Tensorflow API is all about graph construction, but that’s just an implementation detail. A neural network is one possible optimization technique, but if you expose that API users, you’re locking them into a lower-level abstraction than their problem requires.

Machine learning about optimizing functions on a large amount of data. Conal is currently building a denotative ML API that he thinks will not only be more elegant to program with, but be more performant as well. This work builds upon Conal’s denotative approach for calculating derivatives.

Conclusion

In the tradition of Dijkstra’s Goto Considered Harmful, denotative programming promises us higher-quality code with the replacement of various language features, such as statements and mutable state, with a cleaner alternatives, such as recursion and streams. In this way, the denotative approach is a ideal to strive for, not a panacea to solve all problems.

Newfound computational capabilities will likely always be initially expressed non-denotatively, and early adopters of such technologies will be eager to use whatever API necessary for their desired outcome. What’s possible at the edge of computing will always outrun the denotative. Eventually the denotative will catch up to what’s possible today, but by then new technologies will have outpaced our denotative APIs. This one of the cost of the denotative approach: the wait for it to be practical.

In exchange for our patience, we get elegance and simplicity. The denotative confines of the spreadsheet has enabled tens of millions of non-programmers to model complex numerical systems. Denotative programming, extended to handle time-varying values, events, and distributed computing, has the promise to similarly democratize all other aspects of computation, such as user interfaces, web and mobile applications, robotics, and machine learning.

The denotative community can be viewed as a small subset of the functional programming community. It’s mathematical roots scares off potential supporters. Efforts to democratize the denotative approach, such as this essay and flow visualizations, help gain this movement supporters. The more people who see the value in this approach, the more effort will be put behind bringing denotative interfaces to modern technologies, and the sooner the denotative approach can be applied to a computational problem near you.

Further resources

- Let’s reinvent FRP by Simon Friis Vindum

- Conal answers “What is FRP?” on Stack Overflow here and here

- Explicitly Comprehensible Functional Reactive Programming by Steve Krouse

- The Essence and Origins of FRP

- Functional Reactive Animation - the original FRP paper by Conal Elliott and Paul Hudak

- What’s Functional Programming All About?

- The introduction to Reactive Programming you’ve been missing by Andre Staltz

- Why Functional Programming Matters by John Hughes

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Jonathan Edwards for his support and advice. Thanks to Paul Chiusano for pushing me to take on this perspective. Thanks to Antranig Basman, Mariano Guerra, Nick Smith, Mark McGranaghan, Kartik Agaram, Will Taysom, Will Crichton, Vladimir Gordeev, Gregg Tavares, Duncan Woods, Ivan Reese, and the reviewers at the Salon de Refusés for very helpful feedback early drafts of this essay. This essay received a lot of wonderful feedback and went through a number of iterations, which you can get a sense of here.